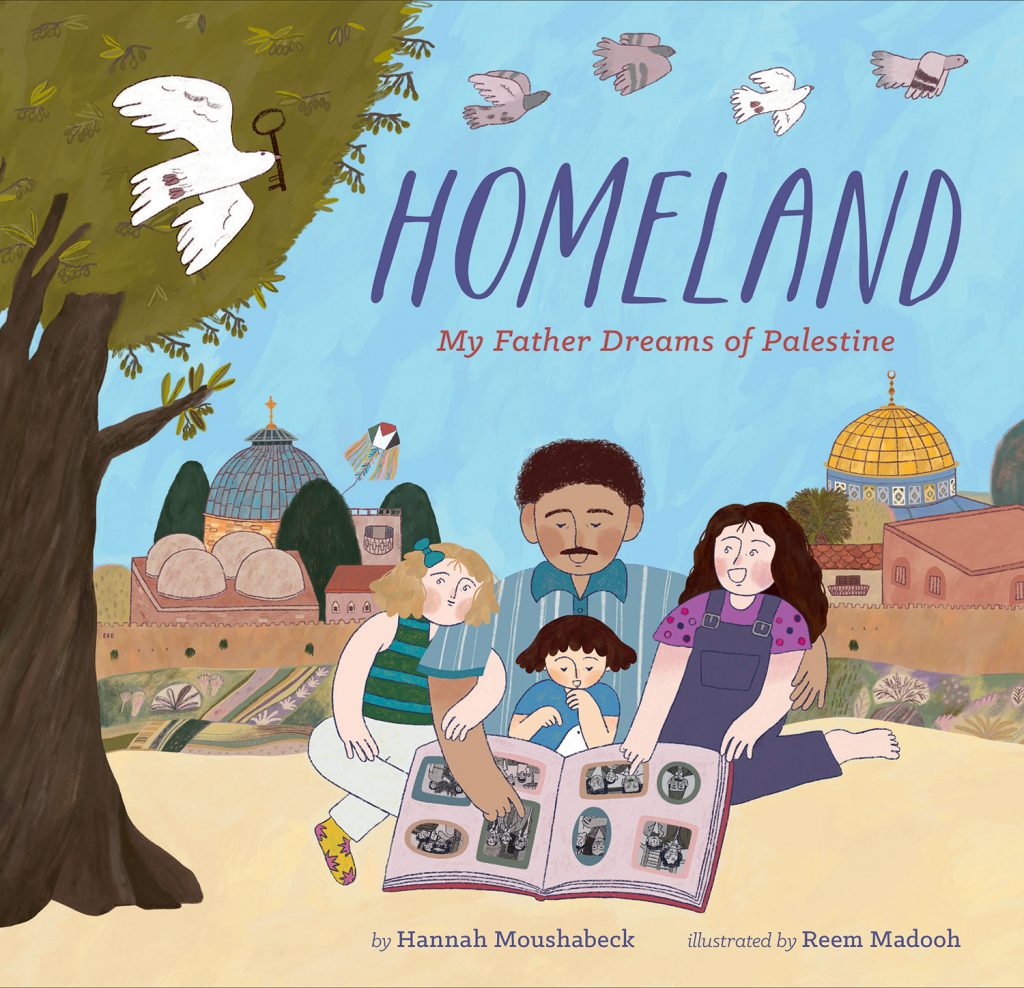

Hannah Moushabeck‘s debut picture book “Homeland: My Father Dreams of Palestine” opens with a tenderly familiar scene: three sisters wait for their father to get home from work so he can tell them a bedtime story. In their shared childhood bedroom in Brooklyn, snug in their pjs, the three sisters listen to their father’s stories of his own childhood, back when he could visit his grandparents in the Old City of Jerusalem in Palestine. On this particular night, he tells them of the last day he saw his grandfather, Sido Abu Michel, who was the head of his neighborhood community in East Jerusalem, called al-Mukhtar, and who owned a café where “[p]oets, musicians, historians, and storytellers gathered to listen to the exchange of ideas.” After a delicious breakfast of fresh ka’ek pulled up by his grandmother, Teta Maria, through the window from a vendor below and after walking through the colorful and lively multicultural streets, past vendors selling “everything from olive oil soap with rose water and heaping bags of za’atar to gold jewelry and embroidered textiles,” Michel and his grandfather arrived at the café, but that wasn’t the end of their journey. Sido then led Michel into a vibrant garden behind the café, home to hundreds of homing pigeons, and “with the help of only a black piece of cloth tied to the end of a long stick,” Sido and the pigeons performed a marvelous spiraling routine, a great circle of birds filling up the sky.

Back in Brooklyn, the image of these pigeons and of the small astonishments of everyday life in Palestine fill the three great-granddaughters’ and daughters’ heads with bittersweet dreams as they drift off to sleep. The three girls have never seen their ancestral homeland firsthand, and their father and extended family live as refugees in exile.

In the world of libraries, librarians and library workers, beyond categorical descriptions of a book’s content and genre (such as nonfiction versus fiction, a picture book biography versus a fantastical tale), another way we like to think of books is as mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors, thanks to the compassionate insights of scholar Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop. Hannah Moushabeck’s delightful and deeply moving picture book biography of her father and her heritage as a Palestinian-American is for me a special shimmer of a story that Dr. Bishop describes as a window made into a mirror:

“When lighting conditions are made right,” Dr. Bishop writes, “a window” — a portal through which we see, and hopefully understand, others — “can also be a mirror” — a portal through which we can see, and hopefully understand, ourselves.

Like Hannah and her sisters, I am a child of an immigrant, a grandchild of a homeland I visited in childhood through my own father’s stories, as well as through my own experiences firsthand. My British grandmother was a character as singular and wondrous as Sido Abu Michel, who held such reverence for pigeons that she often took me to feed them cereal crumbs in the town square. I remember the last time I saw her, almost a decade ago now, and carry the weight of that West Midlands summer’s day with an unending braid of gratitude and grief. And yet, I have visited and can return to my homeland, whereas so many Palestinians are deprived and denied the dignity of truly knowing where they come from due to many appalling factors including ongoing genocide and illegal occupation. Within the profoundly painful contours of this injustice another way to think of books like “Homeland: My Father Dreams of Palestine” arises remarkably in my mind, much like Sido Abu Michel and his iridescent pigeons: books like “Homeland” are also generous, heartfelt invitations — to learn, to listen, to witness, to be enchanted, to get-to-know, to be moved, to act.

As 2024 draws to a close and 2025 begins to fill up our horizons, I invite you to spend time with Hannah Moushabeck’s “Homeland” and to share stories and memories of your own homelands with those you love. What homelands fill up your dreams? Whose homelands do you live on and in now? And what will you do to help others who have been separated from their homelands to return?