Even though sad boy T.S. Eliot (who was born and raised in St. Louis btw) famously wrote “April is the cruellest month,” April is an exhilarating time to be a reader, writer and admirer of poetry: it’s National Poetry Month, y’all! Whether you’re a life-long fan of poetry’s inscrutable magic, or someone who doesn’t quite get what all the fuss is about, I promise that there’s a place for you somewhere in the wide poetry wilds. To riff on the common idiom, there are plenty of fish poems in the sea poetry.

Poems, after all, function a little bit differently from stories and essays. Nonfiction and fiction titles might ask you to figure something out, to learn new information or to consider a unique or unifying perspective. Nonfiction and fiction often, though not always, have discrete answers to questions like “what’s happening or has happened or will happen” or “who is/was/will be this person, this animal, this environment, this object, this culture, this thing?” Poetry isn’t so concerned with answers, or perhaps a better way to put it is that poetry is concerned with both the asking and the answering, with the experience of questioning, of wondering, of (un)knowing. Ultimately, poetry ask-answers its creators and receivers, writers and readers, to participate in a fluid and multidirectional — even multidimensional — process of meaning or meaning-making.

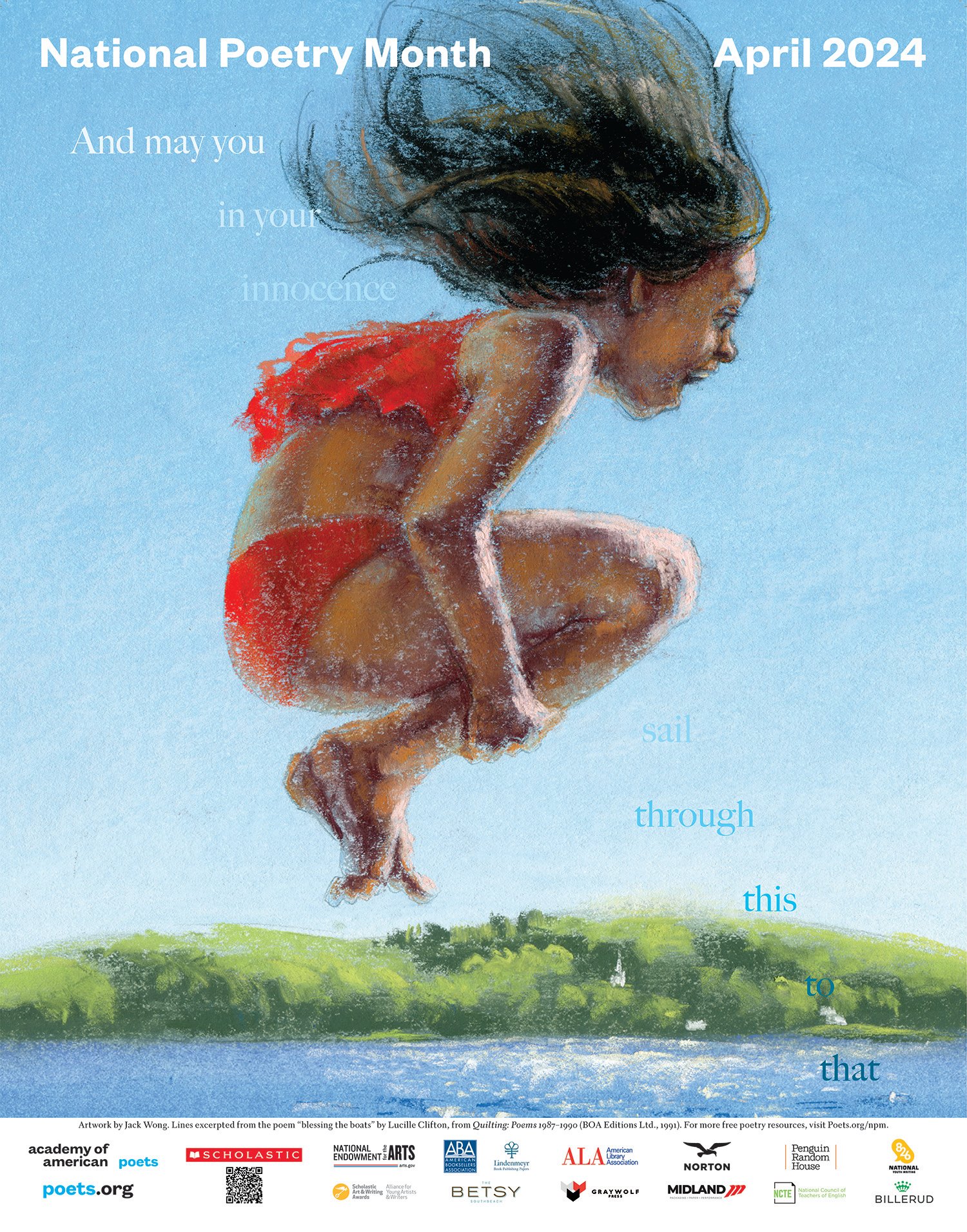

But don’t just take it from me; here’s a brief, yet wondrously packed clip of former Academy of American Poets Chancellor Lucille Clifton — whose poem “blessing the boats” is lovingly adapted on this year’s National Poetry Month poster by children’s book author/illustrator Jack Wong (see above!!!) — sharing her wisdom on the wonderfully thorny question “What is poetry?”:

If poetry is, as Clifton says, not about answers, but questions and wonder, I

So, to open the conversation up, or to help it continue to flow, consider trying out some of the following conversational forms with your pod

Haiku/Tanka

Let’s start off with the short and sweet, though also endlessly wistful and complex, haiku/tanka, a poetic call-and-response form which comes to American poetry from the long and distinguished Japanese tradition. A haiku is a short poem organized in three lines of five, seven and five syllables (5-7-5), often responding to or concerning some kind of occurrence in or revelation from the natural world. For example, you wake up one morning and all of the dandelions have bloomed in your backyard overnight: this would be a lovely (or maybe annoying) experience to write a haiku about.

A tanka is a short poem organized in five lines of five, seven, five, seven and seven syllables (31 syllables total; 5-7-5-7-7). Often, the tanka is separated into two stanzas or sections, with the first stanza being three lines long and the second stanza being two lines, like so:

line one: 5 syllables

line two: 7 syllables

line three: 5 syllables

line four: 7 syllables

line five: 7 syllables

You’ll notice that the tanka includes the haiku form within it as the first section or stanza of the short poem; indeed, the tanka is a kind of extended haiku, a haiku that has some commentary or response following it. If the haiku is a short poem detailing some experience/revelation/annoyance with the natural world, the last two lines of the tanka (also called a couplet) act as some response to the image or experience detailed in the first three lines. This final couplet in the tanka form can also turn attention to the reader, asking the reader a direct question or response. This awareness of a particular reader, a specific person, is important because, historically, the tanka developed in the Imperial Court of Japan as a form of communication involved in courtship. That’s right — we can think of the tanka as a poetic love note!

While historically in Japan tankas were passed back and forth as complete one-line 31-syllable poems, in contemporary explorations of the form, the call-and-response nature has been highlighted by having multiple authors compose the poem together. For example, Poet A/#1 writes the first part of the tanka, which would be the haiku, a short three-lined poem of 5, 7 and 5 syllables, about nature or whatever they’d like. Then, Poet B/#2 writes the second part of the tanka in two lines of 7 syllables each, often responding to something that was said by Poet A/#1. Basically, they’re passing notes but also making it

TRY IT YOURSELF!: Compose a haiku about the first thing you perceived upon waking up &/or walking outside this morning. Or, if you’re a night owl, the last thing you perceived before going to sleep or even a sliver of dream that you remember. Then, send this haiku to a writing friend and hopefully exchange yours for theirs. Pen a responding couplet. Rinse & repeat as long as the vibe feels right.

Cento

The cento comes to American poetry from the ancient Latin tradition. The word translates as “patchwork” or “rag,” and the form functions similarly to a collage or quilt. But instead of using loose scraps of fabric or cut-out images from magazines, to create your cento you’ll use lines of someone else’s poetry (or fragments of language more generally) to write your poem.

I love centos because they are often surprising and weird, as they bring together different voices and dictions. The cento is also a perfect form to write with a group of friends since everyone can bring and share their particular perspective to make a larger work. Here’s a stellar example from contemporary poet Cameron Awkward-Rich:

CENTO BETWEEN THE ENDING AND THE END

Sometimes you don’t die

when you’re supposed to

& now I have a choice

repair a world or build

a new one inside my body

a white door opens

into a place queerly brimming

gold light so velvet-gold

it is like the world

hasn’t happened

when I call out

all my friends are there

everyone we love

is still alive gathered

at the lakeside

like constellations

my honeyed kin

honeyed light

beneath the sky

a garden blue stalks

white buds the moon’s

marble glow the fire

distant & flickering

the body whole bright-

winged brimming

with the hours

of the day beautiful

nameless planet. Oh

friends, my friends—

bloom how you must, wild

until we are free.

One helpful strategy you might use when working on your cento is to amass a word-bank of language that you find marvelous, delightful, exciting, powerful, unusual, terrifying, etc. Basically, any kind of language that catches your attention somehow, that makes you stop for an extra second or longer to ponder. Those are often the best kinds of snippets to source your cento from.

TRY IT YOURSELF!: Spend a little bit of time — a day or week, let’s say — gathering your word-scraps from any and everywhere:

- other writing you love

- conversations you have with loved ones or overhear in the grocery store

- the group chat’s silliest inside joke or hottest take

- old diary entries

- commercials

- songs

- movies

- tumblr posts

- tweets

- etc.

Once you have a page or two (or more!) filled to the brim with these baubles of language, start threading them together. To make the cento even more collaborative, you could create a word-bank with your friends or have each friend contribute their own line(s) to the poem.

Exquisite Corpse

If the cento is a kind of tapestry of language, artfully resourceful and creatively sustainable, we might think of the exquisite corpse as the cento’s chaotic cousin turned into Frankenstein’s monster — the word “corpse” is in the form’s name, after all! Poetry-legend has it that the exquisite corpse emerged out of the eccentric and outlandish minds of the Surrealist Movement as a fun party game. The premise is simple, but can veer wildly very quickly: essentially, you write a poem collaboratively with a group of people, but the catch is that everyone contributes their own part of the poem without knowing what anyone else is writing down.

How does this happen? Traditionally, a piece of paper is folded into however many segments as there are participants in the game. So, if you’ve got thirteen writers, you’ll fold the paper into thirteen parts, accordion-style-ish. Then, the first brave writer writes down their line of poetry in the first slot, something like “Is the pup looking at the swans?!?” This first writer then refolds the paper in some way so that their contribution is obscured from the next writer. The second also brave writer writes down their line, maybe some words such as “the rain picks up the phone.” That second writer then obscures their contribution from the next writer and onward until everyone has had a turn. As you might be thinking, most exquisite corpse collaborations result in much silliness to near incomprehensibility, but sometimes something profound or poignant emerges. In fact, more poetry-legend for you, apparently the name of this kind of poetry game arrived from the following line of poetry that was created while the game was being played: “The exquisite corpse will drink the young wine.”

If folding a piece of paper into many parts is too messy or difficult, you could also go the pulling-a-name-out-of-a-hat-or-bowl route: in this version, everyone simply writes down their contribution on a separate piece of paper and places it into a communal vessel of some kind. Then, as you draw each person’s line(s) of poetry out, you can tape or arrange them together to create your exquisite corpse. Honestly, chaos is the best part of this form, so the weirder and wilder you can make the process, all the better.

Post-Script

My hope in sharing these conversational, collaborative forms is that poetry will feel even the tiniest bit more accessible to you. Even though I’ve felt I was a poet since my earliest memories, I know that sometimes reading and writing poetry can feel isolating and condescending. I’ve been there. If you don’t “get” what the poem is about or how to express the turbulent complication that is having emotions and being a person in the world, you must not be a poet. But that’s just categorically not true, never has been. It’s my secret belief that actually everyone is a poet, in even the tiniest, shyest, quietest, shimmery-est of ways. So, once again, Happy National Poetry Month, wherever and however you celebrate.