“The light, in the morning, in the kitchen, was a thing I did not hate. There was something about the slant of it, the way the room seemed to glow from the floor upward toward the ceiling. I sometimes thought, in moments when I could sit in that kitchen alone, in the morning, with everyone else away, how tolerable it was.”

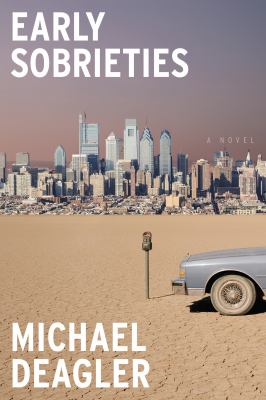

So muses Dennis Monk, ever the optimist, protagonist of California writer Michael Deagler’s introspective debut “Early Sobrieties.” I love this moment, when Monk (who everyone calls by his last name) considers the morning light, softened by how bearable, almost lovely it is. The image reminds me of the opening scene of Zadie Smith’s “The Autograph Man,” when a hungover Alex Li-Tandem notices “a flush of warm light” through his bedroom blinds. Only Monk isn’t hungover — at this point, the 26-year-old is a few painstaking months sober, which is perhaps why this kitchen sunlight very nearly touches his soul, but not quite. Have you ever felt like that? Like the beauty of living was imaginable, but not quite accessible?

scene of Zadie Smith’s “The Autograph Man,” when a hungover Alex Li-Tandem notices “a flush of warm light” through his bedroom blinds. Only Monk isn’t hungover — at this point, the 26-year-old is a few painstaking months sober, which is perhaps why this kitchen sunlight very nearly touches his soul, but not quite. Have you ever felt like that? Like the beauty of living was imaginable, but not quite accessible?

(I don’t mean that accessing this beauty is any more meaningful than being able to imagine it. As we will see, guided by Monk’s meditative narration, imagining is important — having an inkling that some alternate or future version of yourself might be more susceptible to contentment than the current model; making decisions with that self in mind, all the while, day by day, coming to embody that self in imperceptible, precious ways, until one day, the light, in the morning, in the kitchen, inspires an uncomplicated joy.)

Anyways, back to Monk. How can I describe him? Some people make decisions aimed at towering goals; others wake up and ask themselves, “How can I keep my life intact today?” Monk is the second kind… pardon the crude binary.

Monk’s approach to life shapes the novel’s form, which is to say neither has much of a trajectory, at least not in the traditional or expected sense. What Deagler achieves, instead, is a rhythm. Each chapter goes something like this: Monk wanders, Monk ponders, Monk encounters (an old friend, maybe a cousin, occasionally, a romantic interest), Monk settles (a couch, a spare bedroom), Monk stays a while (long enough to pick up some new habits and insights, to reach a meaningful level of comfort or even intimacy with the cohabitant of the moment, to imagine contentment), and then… Monk moves on.

Why does Monk keep moving? What’s his job again — is he still doing that freelance writing thing (or was it food delivery)? Why do people keep offering up their couches for Monk’s indefinite residence? What happened with that woman he was seeing??? Shhhh… don’t worry about it. It’s Monk; he’ll figure it out.

In the universe of Monk’s sobriety, questions about structure and continuity are not all that important, if not wholly beside the point. Some better questions might be: Where is the best place to get a Philly cheesesteak at 2 a.m.? How hard is it to build a desk out of discarded furniture, and will this make her fall in love with you? How is your little brother doing? How can you forgive yourself today?

Tags: prose over plot, Philadelphia, gentrification, addiction, recovery, humor, millennial, character studies, coming of age, unexpected emotional resonance

-Karena