The best stories are the convincing ones — the ones that feel real. The ones with living, breathing characters who contain constellations of motivations and fears, likes and dislikes. Characters who connect with each other in complex and sincere ways. The worst stories are the ones that make you feel like you’re being lied to, or being sold something you can’t quite buy. That’s how a lot of love stories make me feel: Why are these characters so drawn to each other? What do they even have in common? Have they had a single substantive conversation, or are we just going based on chemistry and vibes? Are they being themselves? Are they really interested in understanding, challenging, and considering each other?

Why, out of all the possible, random pairings, is this one special? What makes this romance meaningful? Maybe you’re rolling your eyes at me — I am, too. Reader, I wish it was easier to believe in love stories. I wish I hadn’t found The Notebook completely nauseating (A woman catches a man’s eye at a carnival one summer night and he spends the rest of his life pining for her? Seems weird).

My disbelief doesn’t come from pessimism — it’s really the opposite. I believe in human connection. I believe it makes a life worth living. I believe in love’s ability to surprise us, enliven us, and restore us. So it’s frustrating to watch and read shallow representations of romance, when there is so much more to a love story than attraction and yearning. I don’t want to watch people meet each other, and chase each other. I want to watch them get to know each other, for real.

I watched “When Harry Met Sally” for the first time a couple years ago, and for the second and third times soon thereafter. 12 years of friendship and conversation? Pages and pages of dynamic dialogue between two interesting people, unclouded by infatuation? A dream. All those phone calls and long walks over the years build a convincing bond between Harry and Sally. It makes for a moving moment of confession that reveals one character’s deep understanding of the other.

of friendship and conversation? Pages and pages of dynamic dialogue between two interesting people, unclouded by infatuation? A dream. All those phone calls and long walks over the years build a convincing bond between Harry and Sally. It makes for a moving moment of confession that reveals one character’s deep understanding of the other.

“That’s the final thing you need for a rom-com,” Ira Glass says in an episode of “This American Life.“ “You need for somebody to declare that they see you in ways that you’re usually not seen — maybe you don’t even know yourself.” What is love, if not a mutual, continued noticing — a commitment to see each other in ways we are not usually seen, and to give each other grace when we see something we don’t like?

In his novel “The Course of Love“, Alain de Botton says to “pronounce a lover ‘perfect’ can only be a sign that we have failed to understand them. We can claim to have begun to know someone only when they have substantially disappointed us.”

In his novel “The Course of Love“, Alain de Botton says to “pronounce a lover ‘perfect’ can only be a sign that we have failed to understand them. We can claim to have begun to know someone only when they have substantially disappointed us.”

“The Course of Love” is a novel that explores not so much the start of romance, as its maintenance over time. As de Botton traces Rabih and Kirsten’s trek through love (through marriage, through money problems, through infidelity, through boredom, and through life-altering moments of joy and connection), he leads us to striking revelations about the reality of relationships: “We don’t need to be constantly reasonable in order to have good relationships; all we need to have mastered is the occasional capacity to acknowledge with good grace that we may, in one or two areas, be somewhat insane.”

Novels can capture romance in ways that movies cannot. While films like “When Harry Met Sally” deliver on dialogue, books can convey emotional intimacy and complexity by revealing different kinds of conversations — the inner conflicts of the mind, and all the things felt, yet not spoken between two people.

Sally Rooney’s “Normal People” paints tender psychological portraits of Connell and Marianne, two lovers and friends whose relationship is so intense it often becomes unbearable for their young, permeable hearts. “Normal People” is as much about the things left unsaid as it is about the words actually exchanged. Rooney lets the reader in on the ruminations of our two protagonists’ minds, and occasionally, Connell and Marianne let each other in, too — those are the moments that make this book worth a read (or two, or three). A stunning love story about total emotional intimacy and its power to both ruin and redeem us:

permeable hearts. “Normal People” is as much about the things left unsaid as it is about the words actually exchanged. Rooney lets the reader in on the ruminations of our two protagonists’ minds, and occasionally, Connell and Marianne let each other in, too — those are the moments that make this book worth a read (or two, or three). A stunning love story about total emotional intimacy and its power to both ruin and redeem us:

“For a few seconds they just stood there in stillness, his arms around her, his breath on her ear. Most people go through their whole lives, Marianne thought, without ever really feeling that close with anyone.”

“Being alone with her is like opening a door away from normal life and then closing it behind him… he fears being around her, because of the confusing way he finds himself behaving, the things he says that he would never ordinarily say.”

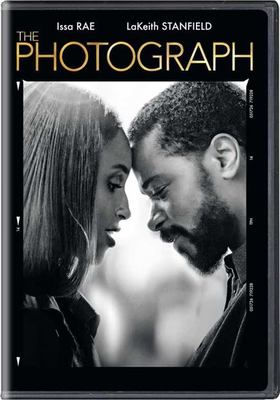

Indeed, emotional intimacy can open up new worlds within and between people. “The Photograph” tells a story of discovery and transformation, braiding two romances into a dazzling tapestry. Michael is a reporter working on a story about recently deceased photographer Christina Eames. His research leads him to Christina’s daughter Mae, a museum curator who is putting on an exhibition of her late mother’s work. While sparks fly in the present, we learn about Christina’s story through flashbacks as she navigates her fraught relationship with her partner Isaac. As the two love stories unfold, one past and one present, “The Photograph” reveals how particular complications and traumas tied to love are often replicated through generations. Even so, it can be worth it to protect our optimism for romance and give it a real chance.

Indeed, emotional intimacy can open up new worlds within and between people. “The Photograph” tells a story of discovery and transformation, braiding two romances into a dazzling tapestry. Michael is a reporter working on a story about recently deceased photographer Christina Eames. His research leads him to Christina’s daughter Mae, a museum curator who is putting on an exhibition of her late mother’s work. While sparks fly in the present, we learn about Christina’s story through flashbacks as she navigates her fraught relationship with her partner Isaac. As the two love stories unfold, one past and one present, “The Photograph” reveals how particular complications and traumas tied to love are often replicated through generations. Even so, it can be worth it to protect our optimism for romance and give it a real chance.

My search for “real” romance sometimes takes me, logically, into the realm of nonfiction. To call Maggie Nelson’s “The Argonauts” a love story would be an oversimplification — it is also an academic work, and a confessional one; a complex, heartrending exploration of sexuality, motherhood, and queer family-making. As Nelson takes on the transformative process of pregnancy, her partner, Harry Dodge, begins testosterone treatment and undergoes a gender-affirming surgery. “The Argonauts“ is a story of care; of love as a survival pact to which we keep each other tethered; of the wonder and relief of knowing another and being known:

“You’ve punctured my solitude, I told you. It had been a useful solitude, constructed, as it was, around a recent sobriety… maniacal bouts of writing, learning to address no one. But the time for its puncturing had come. I feel I can give you everything without giving myself away, I whispered in your basement bed.

If one does one’s solitude right, this is the prize.”