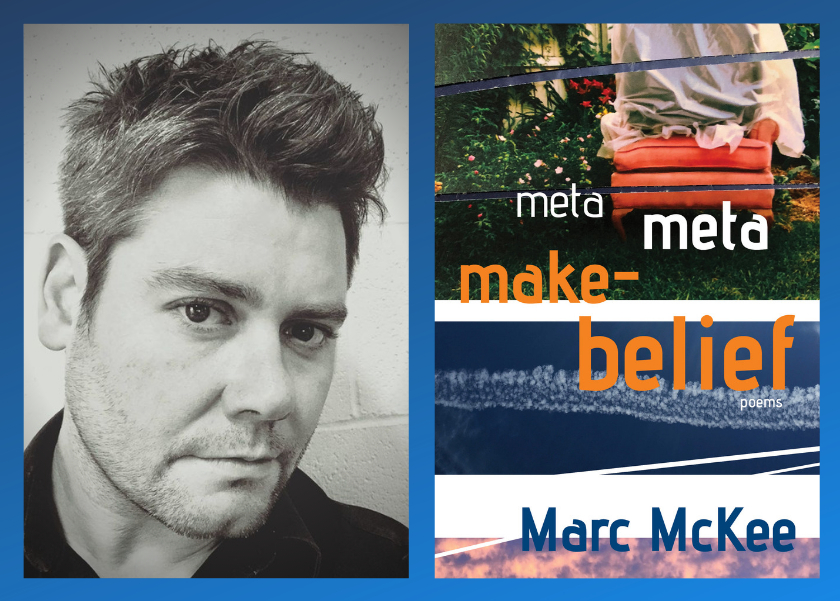

Marc McKee is a Columbia, MO author whose latest book is, “Meta Meta Make-Belief.” It’s a poetry collection full of riffs, tangents, & experiments inspired in spirit by the long tradition in literary and performing arts of calling attention to and celebrating the artificiality and constructedness of art. McKee has authored several other poetry collections, and is currently the managing editor at the Missouri Review. I emailed some interview questions to him, and he was kind enough to take time to write back some answers.

Daniel Boone Regional Library: There are several references to film and film-making in your latest book, including a trilogy of elegies for the late actor Philip Seymour Hoffman. How has film influenced your poetry?

Marc McKee: It would be hard to completely unpack the effects film has had on my poetry, but especially in the beginning of my becoming serious about writing poetry it was really important. Just to give a little context, I was finishing up my undergraduate degree in 1998 when I really started to pursue poetry. There were a lot of exciting movies coming out at that time, and I had wide-ranging tastes, but I really was most affected by movies that swung for the fences, like “Magnolia” or “Fight Club,” as well as being an easy mark for the Coen brothers and later Wes Anderson. Films like “Run, Lola, Run,” “Wings of Desire,” and “Trainspotting,” not to mention secret gems like “The Zero Effect” and “Grosse Pointe Blank,” as well as obvious works of art from Spike Lee, particularly “Malcolm X,” all informed my sense of how to compress and shape content talking about the most expansive and expanding human concerns as the late 20th century collapsed into the early 21st century.

I was reading a lot of poetry, of course, but I was learning that I didn’t want to just apprentice myself to traditional forms or only follow the swirls and eddies of the history of poetry. The energy I wanted my poems to generate, the speed I wanted them to have, the attention to music that spoken language could attain? All of these were glitteringly apparent to me in the movies I was watching, as was a kind of mood or tone I wanted to challenge myself to try to create just using language on a page. There’s no way I can write a poem like “Voice-Over” without diving deep into film noir, and also experiencing the interrogation of that genre in “The Big Lebowski,” not with the express purpose of writing a noir-inflected poem, but by internalizing the language, perspective, and philosophical frameworks and trying to speak to them in a different medium. I had a professor in college who said once that every single frame of a movie meant. I like thinking about the plain truth of that statement and adapting it into a motivation for poems line by line.

For this book, I was moved to write poems about Philip Seymour Hoffman’s characters as a way of elegizing the actor. There was something about his particular power and inhabitation of the body of the character — it’s a whole language, from words and intonations to gestures and even just breaths that just drives me to think of how to make a poetry like that. There’s a moment in “Magnolia” where he’s trying to track down the estranged son of a dying father he is the palliative care nurse for. Desperately trying to get somewhere on the phone with a connection, he has to carry off a line that is an enormous meta wink to the audience. He has to say that he knows that this feels like a movie, where the nurse is searching for the long lost son, but then he says that the reason that this happens in movies is because it’s true. That was an enormous moment for me. It is one of the most crystalline arguments for artifice transmitting truth I have ever come across. It is suggesting that you absolutely need artifice to communicate truth. The reality is, as well, that writing poems like that makes writing poems after that different for me. As it should be.

DBRL: I’m curious about your revision process. How many times do you usually try to revise a poem on average? Do you ever have trouble knowing when a poem is complete?

McKee: I’m curious about my revision process, too. There’s really no set process I go through. It’s just having a particular pile of lines that I dive into and search for life from. My composition process has largely stayed the same since I was in the dumb fountain phase of my early 20s, where I had to write everything down, at all times. I was just so sparked off of language and the ways words could get bent and estranged from the normal information project of most daily speech that I just started piling up copious notes, poem starts, “insights”… Eventually, I would just start a Microsoft Word doc, and just make page breaks between groups of lines and images that felt kind of primordially of a piece, and I would start shaping those pages into poems. Once you get far along enough in that process, you’re naturally in manuscript territory, whether you deserve to be or not. And I lost more than I won at the beginning. There was one summer after a particular romantic disaster that I wrote well over 60 pages of heartbroken sad figure wails. Those pages now exist as a single poem that thieves only the best lines and calls itself an auto cento in my first full-length book, “Fuse.”

I’m also curious about this, because I’ve been on hiatus, a little bit. I have a Word doc that’s right around 70 pages, so I just keep combing through it when I have time, and it’s really a lot like cleaning a house, running a vacuum over everything, and deciding whether it stays or goes. This process will go through anywhere from 15 to 100 cycles, where some poems will be changed dozens of times, and another one will have three lines tweaked before it is confirmed enough to be work I send out to literary magazines. That’s a kind of penultimate editorial stage for me, too. Once enough poems have earned publication credits, I start looking at orders for the manuscript, and start trying to differentiate the poems and starting final edits. Once I get to a place where there’s about 50 – 65 pages that I feel are adequately tight and are being appreciated in the various canyons and switchbacks and cloud cities of lit mags, I start on the final order of the collection. Some people I knew while I was doing my MFA in Houston would work one poem at a time, with docs that were original drafts and 2 – 13 other drafts of a single poem. Not me. I was trying to find a way to think about individual poems and books at the same time, and one big, stupid messy Word doc at a time made the most sense to me. Eventually, revision will get worked out enough that clear stars will announce themselves, and then you do the end stage Word doc, which is really just another way of saying that you have a draft manuscript for a book of poems.

DBRL: You & other University of Missouri alumni had your poems projected onto MU buildings last year for the In Focus: Poetry project. Did you enjoy the process of seeing your poetry on a large canvas? Did the context make you think differently about your work?

McKee: Oh, that was a lot of fun. It was a nice thing to be able to put a little energy into when the plague year was fully establishing itself. It was a wild kind of stress test for the poems, I thought. Because you want to see that parts of your poem can be powerful on their own, and the project really tested that. I was humbled and grateful to be included. It didn’t make me think differently of my work, it actually made me think more clearly about why I put in the work I do to write the poems I write, and what they need to be before they can withstand and contribute to the world. Now, I’m not trying to be grand about what my poems do, but I do think it is instructive to be given a stage like that, and to weigh the work in that context. If anything, it deepened my commitment to my writing, and my gratitude for any time that I am given any space to share it.

DBRL: Read anything good lately you’d like to recommend?

McKee: For the last year, my reading has been limited almost exclusively to submissions to the Missouri Review, where I am the managing editor. I could recommend several dozen poets, young, old, and indifferent who are writing into this moment with bravery, curiosity, and anger, but that’s always the purview of the editorial staff of any literary magazine. Here are a couple of names: Tiana Clark, Leila Chatti, Jamaica Baldwin, Matty Layne Glasgow, Chris Hayes, Heather Treseler, but there are many, many more. Check our website for more leads.

In terms of indispensable poetry books, though, I have a couple of suggestions from the last year or three:

- “Deaf Republic,” Ilya Kaminsky

- “The Tradition,” Jericho Brown

- “Homie,” Danez Smith

- “The Tornado is the World,” Catherine Pierce

- “More than Mere Light,” Jason Koo

There’s more — there’s always more — but this is a good start. I will say one last thing, however.

Not very long ago, one of the most important teachers I had in the journey of my poetry died. There’s just no sentence you can write that can appropriately deal with that species of reality. It’s weird, and it’s wrong that it is the case that Adam Zagajewski has died. I am drawn in many directions by this news, but I’ve got no other public skill set than writing, so that is the way I will try to do him justice forever. In the meantime, so that Adam Zagajewski might be carried in memory, so that his poems and his essays that we need so badly live, I suggest the following books, to start: “Without End: New & Selected Poems” and “A Defense of Ardor: Essays.”

DBRL: Where can readers get a copy of your book?

McKee: Readers can get a copy of my book, or any one of my full-length collections, by ordering directly from Black Lawrence Press. This is the best way to proceed, generally speaking. However, the other best way to get it is to contact your local independent book store, and ask them to order it for you. I’m going to point you towards Yellow Dog Bookshop, because they are the greatest, and because when this plague is banished, we’ll reconvene the reading series I started with co-owner Joe Chevalier, THE NEXT WEATHER.