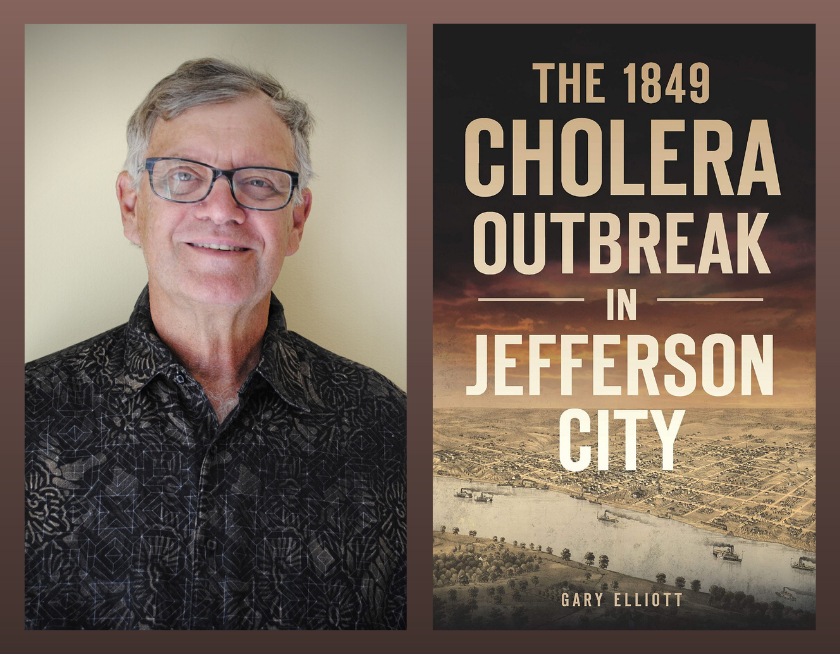

Gary Elliott is a Mid-Missouri author whose latest book is “The 1849 Cholera Outbreak in Jefferson City.” The book is an account of the cholera epidemic aboard the steamship James Monroe, which left from St. Louis, Missouri and arrived in Jefferson City in May of 1849. A resident of Jefferson City, Elliott is a land surveyor by profession, and has previously authored two other books related to Missouri history. I emailed some interview questions to him, and he was kind enough to take time to write back some answers.

Daniel Boone Regional Library: How did you get interested in researching this book? What was the toughest part of putting it together?

Gary Elliott: My interest in the book started when a friend referred me to the City of Jefferson Missouri web page where two sentences mention the occurrence. “A frightening incident took place in 1849, when a ship carrying Mormon church members, some of whom had cholera, landed at the city dock. For two years, the plague-infected residents in the area, paralyzing the local trade.” That was enough to pique my interest. The statement said a lot but provided no details.

The toughest part of putting it together was probably in deciding how much information to include. Do you try to find out everything you can about the passengers and crew that have been identified by name, and include that, or would it be better to just include the minimum necessary for the story-line? The minimal necessary became the route to go because there were so many names that even the minimal information was difficult to find.

DBRL: The two main groups of passengers of the steamship were traveling west for very different reasons. The Philadelphia Mormons were traveling to settle in Utah, while the Jeffersonville Forty-Niners on board were hoping to find gold & wealth in California. How did they get along aboard the ship from your research?

Elliott: There is very little of record that mentions the interaction between the two groups. William Appleby, the leader of the Philadelphia group kept a daily journal but only gives a brief mention that the group from Jeffersonville was on board. Rice McGrew, a 21-year-old from Jeffersonville, also kept a daily diary. When they left St. Louis he recorded that “They [referring to those from Philadelphia] taken as a body are as fine intelligent looking persons as can be found, some of them are very intelligent and refined and would grace any circle of the ladies of the company in particular this is a fact.” I would suspect that the groups kept to themselves and had very little interaction with each other.

DBRL: Can you share one aspect of the 1849 cholera outbreak that reminds you of the present day outbreak of COVID-19?

Elliott: When you look at the symptoms of cholera, as compared to COVID-19, you find that there is very little similarity. Same for the method of exposure. However, I do find one way that they remind me of each other. With cholera, there was a universal lack of understanding of what caused it and the means of its transmission. It wasn’t until 1854 that the source of cholera was first discovered. I think that is similar to today. There are constantly changing opinions of what to do about COVID-19 and how it is spread. Maybe we haven’t reached the point of understanding it enough to fully understand what it is and what to do about it.

DBRL: You encountered a lot of conflicting information in your research, which you detail in the book. Why do you think there were so many discrepancies between the accounts you found?

Elliott: If one looks at the discrepancies from the standpoint of the Indian folk tale of the blind men and the elephant we can understand that each man touched only one part of the elephant and tried to describe it from that perspective. I think the same thing happened in 1849 when several of the accounts are describing only what they saw with very little understanding of the whole picture. For example, some newspaper accounts talk of a group of “Mormon” immigrants, and others talk only of a group of “California gold-diggers.” Many never mention both groups, or any of the other passengers that were not part of one of these groups, in the same article. Also, some of the retellings of the story happened years later when the memories of the storyteller may have waned.

DBRL: What are you most curious to know about the 1849 cholera outbreak that you couldn’t find during your research?

Elliott: The one question I am always asked is “where were the dead buried?” I describe several theories in the book but have been unable to find any conclusive evidence of the exact burial location. Jefferson City, like many small towns affected by the cholera, tried to downplay the disease and therefore the newspapers printed very few details of what was happening. There were more articles printed in the St. Louis Republican than in any of the local newspapers.

DBRL: Where can readers get a copy of your book?

Elliott: The book is available online from Amazon, as well as from the publisher at ArcaidaPublishing.com. It is also available at Downtown Book & Toy in Jefferson City. Additionally, a signed copy can be obtained by contacting me at gelliott10@gmail.com. You can also go to the book’s Facebook page at 1849 Cholera Outbreak in Jefferson City to find more information and to view previously archived videos of past presentations I have given.