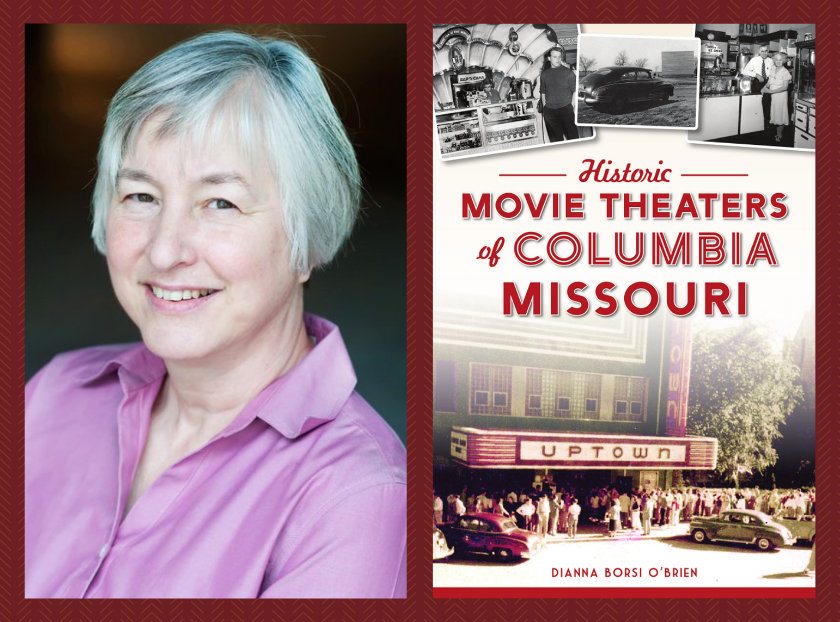

Dianna Borsi O’Brien is a Columbia, MO author whose latest book is “Historic Movie Theaters of Columbia.” The book shares fascinating facts and stories about all 28 movie theaters of Columbia, MO from the 1894 Haden Opera House to today’s Ragtag Cinema. Dianna is a journalist with a passion for local history that she shares on the website CoMoHistoricPlaces.com. Her previous book, “” is a biography of notable local chemist and entrepreneur Charles W. Gehrke. She was kind enough to take the time to be interviewed via email.

Daniel Boone Regional Library: You came to this book project in a roundabout way. Can you walk us through that process? At what point did you think you had enough to create a book?

Dianna Borsi O’Brien: This is the most thought-provoking question! As I say in the book’s acknowledgments, I didn’t really plan on writing a book, but my friend Amanda Staley Harrison, who was a member of the CoMo bicentennial task force, asked me to put together a theater timeline since I’d written a piece in 2010 about movie theater history. At the time, I thought, well, “How hard could that be?” This is always the most dangerous thought I can have because I’ve learned from experience it’s always the start of some kind of quirky adventure. (Ask me sometime about when I went hiking in the Carpathian Mountains.)

Then, to my horror, when I reviewed the 2010 piece on historic movie theaters I spotted a factual error because back then I hadn’t dug into all the contemporary newspaper accounts of that time period. For that 2010 article, I’d interviewed several people who were experts on movie theaters but apparently I’d gotten my facts mixed up or the facts had gotten mixed up over time. But when I spotted those errors, I started researching contemporary newspapers from 1897 and on to 1922. Thank goodness I discovered newspapers.com which made the searching and finding a lot easier. But it also made it a lot easier to fall down research rabbit holes, which are fun but time consuming. (For example, I now know a lot about our local 1919-1920 flu epidemic.) I then started reading up on the movie theater industry because I didn’t have a background in history, movie theaters, or even movies. I had to learn all that along the way. So after a couple of months, I thought I knew a lot about movie theaters and especially a lot about the growth of our movie theater industry. I now realize I knew almost nothing then, but you see, I’d had that dangerous thought — “How difficult could it be?”

That’s when I sent a one-page proposal to Arcadia Publishing/The History Press. That first proposal didn’t even have a word count on it because I truly didn’t know what I was doing. Well, I was surprised when I got a reply a day or so later saying they’d like to publish the book and could I send an outline. Then I started to scramble to pull information together and I realized that the book could have this really lovely literary arc of starting in reused buildings of people just coming together to see something amazing to ending up the same way with the Ragtag Cinema in a reused building with people coming together to see something amazing. So a month later, I finally had an outline written and I think it was then I thought it could turn out to be a book — a short book, but a book nonetheless. The joke, as it turned out, was on me because when I finished the book, I had to cut it by several thousand words. By the way, I still haven’t done a formal movie theater timeline!

I want to mention one other thing about the process. My process was messy. It involved making my own hand-drawn maps of downtown so I could envision where all the movie theaters were, and where they moved to and from over time so I could try to understand what was happening in Columbia during the various time periods. For example, the Airdrome at first was between Sixth and Seventh streets, but as Columbia’s business core continued to converge on Ninth Street, the Airdrome moved closer to that area. I made extensive spreadsheets tracking the city’s population growth, the number of movie theaters, how many theater seats were available, and the university’s increasing student numbers. I created a timeline of sorts with national events such as the 1918-1919 flu pandemic which closed down local movie theaters and took the life of the son of one of the early movie theater owners. I also stuck any pictures of the movie theaters and their owners I could find on my bulletin board to keep me focused.

I don’t think it matters what your process is or how you go about a book. I think what matters the most is sheer persistence and the belief that somehow you can do it. Of course, I had lots of people cheering me on, but one phrase that did keep me going came from a plaque I still have, “She believed she could, so she did.” Knowing what you are doing isn’t nearly as important as being willing to learn and to keep going.

By the way, this book also led me to another adventure that started with the same line, “How difficult could that be?” Trevor Harris, I and several others have started a new nonprofit dedicated to saving historic buildings. CoMo Preservation now meets monthly and is working to establish our 501c3 status and has its own facebook and website at comopreservation.org.

DBRL: Can you name one local theater that you wish had been saved from demolition?

O’Brien: The one local movie theater I grieve the most is the loss of the interior of the Hall Theatre. The shell of the building still exists and inside the upper part of the proscenium exists, but the orchestra pit is gone, as is the stage and the dressing rooms. I know from my research that the dressing rooms were quite swank and must have been impressive, but sometime between the purchase of the building by local jeweler Max Gilland and him leasing it to Panera Bread, the floor was leveled, the balcony was removed, and other damage was done. This is particularly sad because you can still see the beautiful teal green and pink edges of the stage opening above where the orchestra pit must have been. So the theater has been saved, but the interior bits left make me so sad that we lost all this beauty and history.

A lot of people don’t know that when the Hall opened in 1916 and for decades afterward, it was segregated. African American moviegoers had to sit upstairs and having that balcony still in existence would give everyone insight into that dark but important part of our city’s history. So I mourn that movie theater every single time I walk downtown. I think it would make an amazing place to have a downtown Columbia museum or a branch location of the Boone County History & Culture Center. Every day I hope that the owner or some other buyer will decide to recreate it, or at least give it life in some fashion.

DBRL: Many of the early theaters you write about were interconnected in various ways. Why do you think this was the case? Was it partly due to the nature of the movie business, or was this just due to typical small town connections?

O’Brien: These connections fascinated me too. I think the connections in the early years were a function of the small population of Columbia. Remember, in 1910, there were only 9,662 people, but from 1900 to 1910, we had eight movie theaters open, so movie theater men were moving around like chess pieces. Also, it was a booming business, much like Silicon Valley in our recent history, and so I think people looking to make their fortunes just hopped on the bandwagon. At one point, a newspaper article suggested that the local movie theaters were taking in more money per day than the banks. Some of the men were indeed connected.

The most interesting person I wrote about was Homer Gray Woods, who went from a movie theater in Centralia to managing the short-lived, racist Negro Nickelodeon in 1909 — the only Columbia movie theater started and funded by MU students — to managing the Star, the Hall and the Varsity, which is now The Blue Note. He literally gave his life to the movie theaters. His half-brother, Tom C. Hall, is the person who built the Star, the Hall and the Varsity, but he came into the theater industry as a capitalist (the occupation he listed in a census record), and entered the business after his brother Woods. But not everyone who got into the movie industry found it to their liking. One man kept berating moviegoers in his ads and he later left the industry and went back to his original job with the telegram business.

DBRL: Is there a good memory from attending a local theater that you’d like to share?

O’Brien: You might laugh but I don’t go to the movies much except with my granddaughter and her family who all live on the East Coast! But my favorite memory of a local movie theater is from when my granddaughter would come to visit us and we’d walk over to Forum 8 from our house. It’s nice to be able to walk to a neighborhood theater much like people used to be able to do when the majority of Columbia residents lived near downtown before the 1940s and 1950s move to suburban living.

DBRL: Your first book was a non-fiction biography that also included elements of local history. How did the research and writing differ between the two books?

O’Brien: The first book, “,” started with Charles W. Gehrke who wanted his biography written so it started from a personal perspective and I gathered historic facts as I went along to confirm and enrich what he told me. The movie theater book started with the historical facts and then I worked to find people to flesh out the stories. I always think all writing should be bones and flesh — bones are the hard facts and the flesh are the people involved.

My favorite part of writing this book was getting to know people like Harold Nichols, who died only a few months before the book was published. He was a gift to me because he remembered so far back, and recalled the facts with such clarity I could confirm what he told me through other sources. He was just an incredibly sweet person who seemed so happy to be able to share his story of working in the movie theaters from 1939 and for nearly six decades.

DBRL: Read anything good lately you’d like to recommend?

O’Brien: One of my most recent favorites have been two books I read for the 2022 Read Harder Challenge, “The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating” by Elisabeth Tova Bailey, and the “Genius of Birds” by Jennifer Ackermann. Both of them interweave factual information with the author’s story. I admire when an author can put herself in the book but still impart factual information.

DBRL: Where can readers get a copy of your book?

O’Brien: My book is for sale from my own website CoMoHistoricPlaces.com, and in brick-and-mortar stores like the Boone County History & Culture Center, Skylark Bookshop, Yellowdog Bookshop, Blue Stem and the State Historical Society of Missouri downtown.