“Rocketry may not be my True Will,

but it’s one hell of a powerful drive.

With Thelema as my goal

And the stars my destination and my home,

I have set my eyes on high.”

Jack Parsons, Genius, Eccentric, Occultist, & Rocketeer

I am not a poetic man; both in the sense that I don’t write poetically (despite some of my readers’ assertions. I posit that, as a prose writer, I write prosaically in the most literal sense), and also that I do not often indulge myself in poetry. Not through any disdain for the medium, mind you, but simply a lack of motivation or interest. But sometimes, a book can trick you into reading extraneous literature (and poetry, as it turns out) in order to deepen your understanding and appreciation of the original text. Many great literary novels either require an intimate knowledge of other books within the author’s purview, or require a rather large desk on which to lay out several tomes at once to cross-reference the many inferences to other works. This is not necessarily a bad way to read, but it is a tad more academic than curling up in an armchair or bed to engross oneself in a story.

Perhaps due to said engrossment being pivotal in certain modes of literature, this style of reading less often occurs in genre fiction like sci-fi. However, this past National Poetry Month, which this blog post is regrettably three days late for, found me reading not one, not three, but two science fiction novels with a focus or foundation on poetry and classic literature: Dan Simmons’ “Hyperion” and Alfred Bester’s “The Stars My Destination.”

The Canterbury Tales of the 28th Century, with Asides by John Keats: Dan Simmons’ “Hyperion”

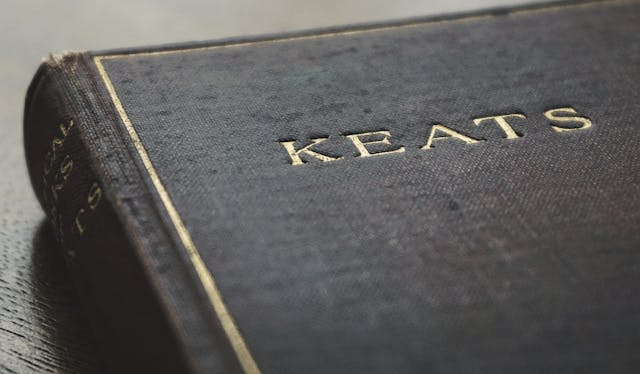

“These crystalline pavilions, and pure fanes/Of all my lucent empire? It is left/ Deserted, void, nor any haunt of mine.” writes Romantic poet John Keats in his unfinished poetic epic “Hyperion.” Which is, of course, where Simmons derives the title of his science fiction novel (and the planet on which it takes place), as well as the descriptors of the mysterious Time Tombs, which are the ultimate destination of the novel’s pilgrimatical main characters.

The world of Dan Simmons’ “Hyperion Cantos,” of which “Hyperion” is the first of four, is immersed in literary reference and inspiration. Keats’ body of work, as well as the events of his life and personage, factor heavily into every aspect of the novel; The planet Hyperion, named from the epic poem, is capitoled by a city named Keats, if the referential nature of the novel was not already readily apparent. Keats’ poetry influences character names, like the private investigator Brawne Lamia, named for both the poet’s muse Fanny Brawne and his poem dedicated to the eponymous snake nymph, Lamia. His poetry inspires the poet Martin Silenus to pursue his own epic cantos of poetry, before his muse, the mysterious Shrike, deprives him of inspiration.

Beyond Keats’ heavy hand upon this novel, Simmons also derives the story’s format and premise from another English writer: Geoffrey Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” forms the backbone of the pacing and format of the novel, as it follows a not dissimilar group of travelers on a pilgrimage. Where the pilgrimage itself is built as the frame of the story, the actual meat and potatoes of the novel come from the characters explaining their impetus for traveling on this perilous journey. Each character gives a vignette into the world Simmons has built: A Catholic priest on a journey to find his mentor, a poet from Old Earth who has lost his muse over the centuries, a former military officer who became an anti-war activist after his experiences on Hyperion, and other viewpoints give breadth and depth to Hyperion and the Hegemony of Planets at large. Much as Chaucer focused on what had brought the Knight, the Reeve, and the Wife of Bath together, Simmons is telling a retrospective tale of what brought these characters to the present, rather than following them into the future.

The book was pitched to me by a friend as “A literary nerd decided to write a sci-fi novel,” and it undoubtedly delivers on that front. But, for all its steeping in Keats’ poetry and Chaucer’s frame story narratives, it doesn’t skimp on the science fiction aspect of its personality either; the book is chock-full of interplanetary travel, the time-debt accrued by those who venture to the stars, leaving them unmoored from time, grand and far-reaching artificial intelligences operating at all scales of life, and the variations on humanity that occur as we send ships to far-flung stars, and the disparate cultures that emerge (or, perhaps, endure) through the ages. “Hyperion” is an epic in its own right, and comes highly recommended from this science fiction reader.

“The Count of Monte Cristo” by Way of William Blake’s “The Tyger”: Alfred Bester’s “The Stars My Destination”

“Gully Foyle is my name/ And Terra is my nation/ Deep space is my dwelling place/ And death’s my destination.”

So speaks the main character of Bester’s novel upon his first appearance (adrift in the void of space, running low on supplies, and full of desperation and the seeds of revenge), making reference to a popular quatrain poetic form used in the 1700s onwards for people to poetically name themselves, their home, and their ultimate destination (though most used “Heaven” rather than Foyles more fatalist “death”). It is a form that is no stranger to literary works as well, as it features also in the inscrutable James Joyce’s work “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.”

Beyond this form, Bester’s writing also takes a special interest in Blake’s “The Tyger.” Originally referenced in the book’s original title, “Tiger, Tiger!,” allusions to Blake’s beast of fearful symmetry become literal, when Foyle is tattooed and scarred by his would-be rescuers and whose face takes on the striped appearance of a tiger. This visage is put to use by Foyle, who hides himself behind his new visage, among other personas, and hatches a plan of revenge against those who had led him down this disastrous path through space, embodying the “deadly terrors” of the poem’s subject.

Speaking of revenge, Bester’s other inspiration for this novel is obvious from quite near the beginning: Foyle’s arc of betrayal, exile, disguise, and revenge so closely mirrors Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo,” one could mistake it as an adaptation. Or, perhaps this was apparent to me, as “Monte Cristo” is one of my favorite classic novels, and so I fulfill that first requirement of allusory reading that I mentioned in my introduction. However, by placing the framework of that story in a new setting, and hedging it within deep science fiction, Bester provides a novel spin on the story, to where the allusions to Dumas come across as tribute and admiration, rather than mimicry.

If I have learned anything from these novels, it is that poetry is not a form locked in the past, or sequestered into artistic niches that stand apart from other literature, but that its literary cant can thrive in otherwise genre-heavy mediums, and pull those works into a liminal space between the high arts and the pulp. So, I ask of you, dear reader, in what distant deeps or skies shall we find our next literary adventure?