Oftentimes, words alone can only communicate so much. Prose authors will explore the limits of their medium by weaving together literary techniques like metaphor and personification for deliciously descriptive passages. Take for example this description of monsoon season from Arundhati Roy’s “The God of Small Things:”

“Heaven opened and the water hammered down, reviving the reluctant old well, greenmossing the pigless pigsty, carpet bombing still, tea-colored puddles the way memory bombs still, tea-colored minds. The grass looked wetgreen and pleased.”

But are there other methods beyond pure text for authors to communicate? The answer is an emphatic “yes!” And do fiction creators have sole claim to them? Why, soitenly not! You can find graphic nonfiction sprinkled throughout our collection on all sorts of topics, but the number of biographies and memoirs may surprise you most.

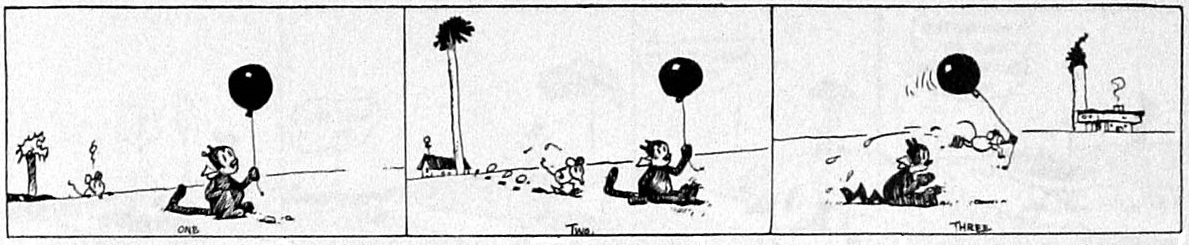

As Scott McCloud puts it, comics as a medium — that is *achem* “juxtaposed pictorial and other images [i.e. letters] in a deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer” — expands the possibilities for audience immersion, authorial expression and creative storytelling. To boil it down, he means a storytelling method that mixes text, illustrations and other images. Often the term “comics” conjures up the image of the Sunday funnies or a glossy Marvel serial, but don’t let such iterations limit you understanding of this “pictorial-narrative” method.

For an innovative, easily digested presentation of comics theory entirely in graphic format(!!), check out McCloud’s “Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art.” A cartoon version of the author explains what comics is, the anatomy of comics and how the medium creates meaning. For example, the “gutter,” i.e. the space between comic panels, to him provides the “magic and mystery” that comics have. Here the reader participates in “closure” or narrative continuity between the “jagged, staccato rhythm of unconnected moments [panels].” The gutter allows the author to not only play with the passage of time and changing perspective but also embrace their audience. It’s here that the readers must consistently imagine in their own way that which is not immediately portrayed. In McCloud’s words, “to kill a man between panels is to condemn him to a thousand deaths.”

I also recommend Hillary Chute’s “Why Comics?: From Underground to Everywhere” for her detailed history and comics analysis organized by common subgenres like disaster/war, feminist, superhero, queer and disability narratives. Of the seminal works she discusses, many portray real events, often in the creator’s own life, ranging from the personal to the global. You’ll come away with a broad understanding of both the ever-sprawling world of comics and, particularly, the effectiveness of the medium for authors and journalists portraying their truth. (You’ll also understand why I’m using “comics” as a singular noun in her introduction: “Comics for Grownups?”)

Here are a couple works that, in my humble opinion, prove the value in graphic nonfiction. These titles seized my attention and made their indelible marks. Seriously, “Blankets” had me weeping at Gate A4 in Lambert International Airport.

“Blankets” by Craig Thompson

Thompson’s intimate coming-of-age memoir portrays his rural Wisconsin upbringing in an abusive and repressive household. As he grows older, we see his faith develop and eventually questioned while he also experiences the aches and exhilarations of first love. Through graphics, Craig’s inner torments become visible; his character’s figure is abstracted enough to allow us readers to intensely identify with him.

“A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge” by Josh Neufeld

Neufeld uses comics for journalistic ends, depicting the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina and its aftereffects on five different families as well as countless others along the way. Perhaps the most effective, yet difficult scenes to take in were those at the infamously chaotic Convention Center. Between the dense sea of bodies, close-ups of exaggerated beads of sweat and the stomach-churning state of the inundated bathrooms, his illustrations show just how deteriorated the conditions became by September 1, three blistering days after the storm. Here thousands of neglected New Orleanians were forced to tirelessly wait for food relief, water and eventually evacuation.

Neufeld, like many nonfiction creators before him, makes the book self-aware in the end by portraying his own role of researching and conducting phone interviews with the main characters. This choice reasserts that this narrative is grounded in real experience, perhaps rendering it more poignant. I also appreciate his clever use of monochromatic palettes, aptly shifting the base shade between days, scenes, and sections. For example, the coloring for that toxic scene at the Convention Center, to me, suggested of bile. The day before as tensions and temperatures rose, the base shade was pink-red. These stylistic choices can make for an, at times, unsettling experience, yet this kind of affective response is part of the appeal nonfiction comics have for devoted readers.

A few more recommendations:

- Art Spiegelman’s classic “Maus I A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History” & “Maus II A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began” as well as the omnibus companion “MetaMaus”

- Catel & Bocquet’s “Josephine Baker”

- Anything by Joe Sacco or Guy Delisle

- David Small’s “Stitches”

- Joyce Brabner, Columbia’s own Frank Stack & Harvey Pekar’s “Our Cancer Year.”

Image credits: George Herriman, Krazy Kat via Wikimedia Commons (public domain); Jgmz, Screenwriting (cropped) via Wikimedia Commons (license)