In May 2023 I was diagnosed with a disorder with no cure and no end — just a few debatable treatment options and a sparse online community. Still, I was relieved to get an answer to a question I’d been asking for about a decade. It’s been over a year since a specialist identified my spasmodic dysphonia (a voice disorder, originating in the brain), and, now, I have new questions to ask: How do I carry my diagnosis with honesty and vulnerability, without letting it flood my identity? How do I stay hopeful through the grueling experiment of treatment? How do I help my loved ones understand?

Books have helped soothe the ache of these questions. Maybe they can do the same for you, whether your diagnosis is one of chronic illness, disorder, neurodivergence or any other ongoing condition.

In their book “Long Illness: A Practical Guide to Surviving, Healing, and Thriving,” Meghan Jobson, M.D., Ph.D. and Juliet Morgan, M.D. make space and offer guidance for these questions of survival. “Long Illness” is a love letter to the millions of people living with chronic illness (a number that is only growing, as the long-term effects of COVID-19 come to light). Theirs is not a book about overcoming illness; rather, Jobson and Morgan offer affirmation and empowerment in the form of survivor stories, journaling prompts and more.

In their book “Long Illness: A Practical Guide to Surviving, Healing, and Thriving,” Meghan Jobson, M.D., Ph.D. and Juliet Morgan, M.D. make space and offer guidance for these questions of survival. “Long Illness” is a love letter to the millions of people living with chronic illness (a number that is only growing, as the long-term effects of COVID-19 come to light). Theirs is not a book about overcoming illness; rather, Jobson and Morgan offer affirmation and empowerment in the form of survivor stories, journaling prompts and more.

For readers with hearts more easily reached by memoir, John Hendrickson’s “Life on Delay: Making Peace With a Stutter,” is a striking read. While it is inaccurate to describe speech and voice disorders as diseases, certain hallmarks of stuttering are characteristic of many long-term illnesses — mysterious in origin, variable in presentation and resistant to treatment. Hendrickson tells the story of how he made peace with his stutter to become a successful journalist (one with a Joe Biden feature on his resume), and, more importantly, a balanced human grounded in gratitude.

inaccurate to describe speech and voice disorders as diseases, certain hallmarks of stuttering are characteristic of many long-term illnesses — mysterious in origin, variable in presentation and resistant to treatment. Hendrickson tells the story of how he made peace with his stutter to become a successful journalist (one with a Joe Biden feature on his resume), and, more importantly, a balanced human grounded in gratitude.

Some disorders are apparent early on; others strike much later. Lauren Marks takes us through the sudden onset of her aphasia in “A Stitch of Time: The Year a Brain Injury Changed My Language and Life.” Her story holds a similar irony to Hendrickson’s; he was a reporter with a stutter and she was a writer and doctoral student stripped of her ability to use or process language. Isn’t it strange, how one’s core passions and core struggles are so often entangled?

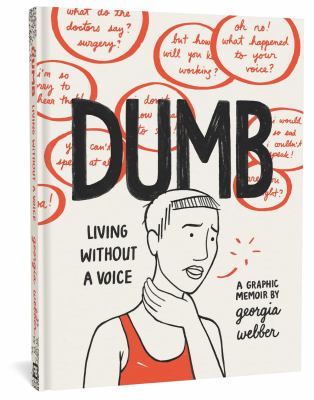

The same is true for singer Georgia Webber, the artist behind the graphic memoir “Dumb: Living Without a Voice.” One day, it becomes painful for Georgia to use her voice, and so begins a long journey of seeking support (from both systems and friends) and getting to know herself in a quieter, kinder way. “Everything Is an Emergency: An OCD Story in Words & Pictures.” by New Yorker cartoonist Jason Adam Katzenstein is another skillful graphic memoir that opens a window into a commonly misunderstood condition, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The same is true for singer Georgia Webber, the artist behind the graphic memoir “Dumb: Living Without a Voice.” One day, it becomes painful for Georgia to use her voice, and so begins a long journey of seeking support (from both systems and friends) and getting to know herself in a quieter, kinder way. “Everything Is an Emergency: An OCD Story in Words & Pictures.” by New Yorker cartoonist Jason Adam Katzenstein is another skillful graphic memoir that opens a window into a commonly misunderstood condition, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

While it is important not to pathologize developmental differences, it can be worthwhile to consider the often shared experiences of those with bodily illnesses and those who are neurodivergent — the alienation, the weight of carrying a mystery within you, the desperation for someone to help unmask and name it.

Anand Prahlad, director of creative writing at the University of Missouri, reckons with such feelings in his memoir “The Secret Life of a Black Aspie.” Generously and with breathtaking honesty, he unwinds his experience of having Asperger’s and being Black: “I’m telling you because I want to put my mind on display, like a painting on the wall.”

and with breathtaking honesty, he unwinds his experience of having Asperger’s and being Black: “I’m telling you because I want to put my mind on display, like a painting on the wall.”

These memoirs have one thing in common: the authors’ healing never happens alone. The same is true for my story — I am lucky to have friends who lean in to listen, who will participate in my theatrical voice therapy exercises, and who are happy to communicate with me by passing a notebook back and forth when my voice is tired, but I still have a lot to say.

If you struggle to do things that people around you seem to do effortlessly, know that your needs deserve compassionate acceptance and accommodation, from both yourself and others. Know that there is a movement growing around you. This brings me to my last recommendation: Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s “Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice,” a revolutionary text that will call you out, call you in and call you towards a vision of mutual, interweaving care.

In Piepzna-Samarasinha’s resounding words, disability justice means “asserting a vision of liberation in which destroying ableism is part of social justice. It means the hotness, smarts, and value of our sick and disabled bodies. It means we are not left behind; we are beloved, kindred, needed.”