It’s common knowledge that during the American Civil War President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, legally freeing millions of African Americans who were enslaved in the Confederate states, on January 1, 1863. But the story did not simply end then; there was still much to accomplish around the nation in fully abolishing the 400-year-old system of slavery, one which long predated nationhood in some of the earliest colonies. To start, border states like Missouri that permitted slaveholding while remaining in the Union during the war were not subject to Lincoln’s executive order. It was up to those individual states to commit to emancipation, and the Missouri state legislature secured the abolition of slavery the year after. Another challenge was spreading word of the Emancipation Proclamation to areas in rebellion, particularly remote parts of the “Old Southwest” where Union armies had not campaigned.

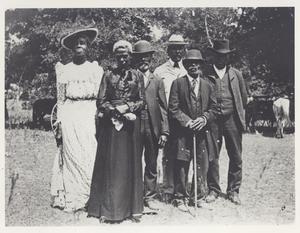

Two months after the Confederacy surrendered at the Appomattox Courthouse, hundreds of thousands of Black Texans labored in chattel status until the arrival of General Gordon Granger in Galveston, Texas, who on June 19, 1865 publicized the reality of emancipation. The ensuing jubilee set the precedent for annual Juneteenth celebrations, which often involve parades and rodeos, storytelling, pageants and barbecue cookouts complete with red pies and red drinks (see chapter 13). According to the Texas State Historical Association, “The first broader celebrations of Juneteenth were used as political rallies and to teach freed [male] African Americans about their voting rights.”

Because slavery was abolished so sporadically around the nation, there are several different days across the states when Americans celebrate emancipation, ranging from April 16th in Washington D.C. to September 22 to coincide with the anniversary of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Case in point, in her cookbook “The Taste of Country Cooking” Edna Lewis reminisces about such celebrations in Freetown, Virginia, a hamlet begun by former slaves in her family, and shares recipes for an autumn Emancipation Day fest. Juneteenth still remains the most popular, especially with renewed interest in the holiday since the 1960s. Isabel Wilkerson writes in “The Warmth of Other Suns” about the millions of African Americans who left the South during the Great Migration and brought along Juneteenth traditions to their new communities. In fact it was at these festivals where she met participants to interview for oral histories in her book. While Juneteenth is not yet a federally recognized holiday, Missouri officially designated June 19th as “Emancipation Day” in 2003. People from around the state gathered this past weekend for festivals in St. Louis, Kansas City, Jefferson City, Mexico and Fayette. This afternoon folks are flocking to Columbia’s Douglass Park for a massive water fight.

In the spirit of that 2003 resolution, here are a few additional resources that celebrate Black heritage and reflect on both the meaning of freedom and the legacies of enslavement in our country.

- Slave Narratives in text, as audio recordings

- “Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery” – Seymour Drescher

- “American Anti-Slavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation”

- “The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States” – Ira Berlin

- “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877” – Eric Foner

- “W.E.B. DuBois’s Data Portraits | Visualizing Black America: The Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century”

- “Official Guide to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture”

- “Stories From the Heart: Missouri’s African American Heritage”

- “The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South” – Michael Twitty

- “Black Roots: A Beginner’s Guide to Tracing the African American Family Tree”

- “A Seat at the Table” and “When I Get Home”- Solange

- Black Culture and History Guide – DBRL

How will you observe Juneteenth this year?