Once a month, Columbia Public Library hosts Silent Book Club in the Quiet Reading Room. If you’re thinking about attending and wondering what to expect, keep reading!

During the day, the Quiet Reading Room is an aquarium of air and light. At night, the glass room feels more like a spaceship, suspended in the dark. (From far away I imagine it glowing like a night light.)

It is Tuesday evening, nearing six o’clock. The first part of your day is over, and the next part is beginning, here, on the third floor of the library.

A right at the top of the staircase, then all the way down the floor. In the Quiet Reading Room, someone has arranged ten plush chairs in a circle. A few people have already arrived. You stop by the coffee and tea cart before taking a seat. (A sip, a sigh, a settling of the mind.)

“Silent Book Club ® is a global community of readers, with more than 1400 chapters in 54 countries around the world led by local volunteers. SBC members gather in public at bars, cafes, bookstores, libraries, and online to read together in quiet camaraderie” (silentbookclub.com).

A library employee thanks you for coming. At six o’clock they greet the group; the circle has filled with readers. Everyone takes turns introducing themselves and the books they’re reading this evening: historical fiction, sci-fi, biography, romance; paperbacks, hardcovers, audiobooks, tablets.

You hold your book up towards the group. (Smiles of recognition, interested looks.) The library employee sets a timer for one hour. Now, the reading begins.

The silence feels sudden at first, but you find that the absence of conversation makes room for other sounds: raindrops on windows, pages turning, your own breath. Slowly, focus finds you. The minutes stream together; the hour rinses the mind.

It is just past seven now. The library employee concludes the reading and welcomes the group back into the world of conversation. The person next to you is reeling from a plot twist. The person next to them is exasperated — the lovers are taking too long to confess.

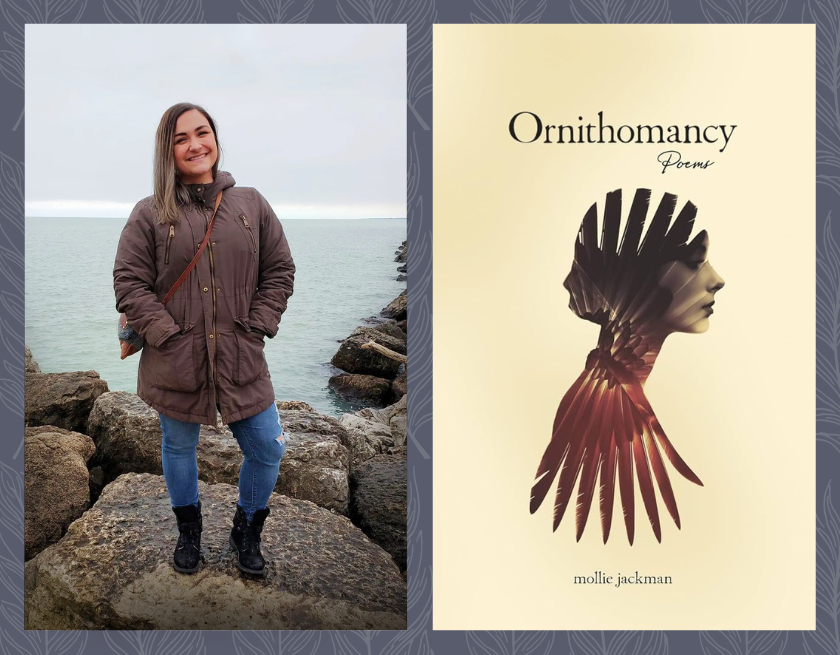

Someone across the circle holds a book of poems, and they read their favorite one aloud. You share that you’re enjoying your book, and someone asks for the title so they can write it down.

The next Silent Book Club at Columbia Public Library is scheduled for Tuesday, Jan. 28 from 6 to 7:30 p.m. You can find upcoming sessions on the live events calendar. No registration required.