It has been 100 years since the Spanish Flu pandemic. The flu, which was first recorded in March 1918, killed 50 to 100 million people by March 1920. It coincided with the First World War, which often overshadows the pandemic in our collective memory. Despite the fact far more people worldwide died of the flu, the two may be inextricable. Laura Spinney examines that connection in the recently published “Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World.” Spinney writes, “Conflict makes people hungry and anxious; it uproots them, packs them into insanitary camps and requisitions their doctors. It makes them vulnerable to infection, and then it sets large numbers of them in motion so that they can carry that infection to new places. In every conflict of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, more lives were lost to disease than to battlefield injuries.” Spinney also suggests that memory for a pandemic simply takes time to develop because “… it’s not so easy to count the dead. They don’t wear uniforms, display exit wounds or fall down in a circumscribed arena. They die in large numbers in a short space of time over a vast expanse of space, and many of them disappear into mass graves, not only before their disease has been diagnosed, but often before their lives have been recorded.”

Although there were a many great writers of the day who were directly affected by the flu, very few of them wrote directly about the experience. The subsequent malaise may have left a more lasting impression. Virginia Woolf commented on this lack of literature in her work “On Being Ill” when she wrote “Consider how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing… , when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.” Many people post-flu were left with lingering issues including depression, hallucinations, delusions, dementia and schizophrenia. “Kafka, the Years of Insight” by Reiner Stach highlights Franz Kafka’s life from 1916 to his death in 1924, leading into the war as he fell ill with the flu and woke up in a different country. Another neurological condition that was associated with the pandemic was called encephalitis lethargica (LE) or “sleepy sickness.” Some patients suffered from LE for decades. Their eventual waking was chronicled by the British neurologist Oliver Sacks in his book “Awakenings.”

The 1918 pandemic experience has also seen more recent analysis in literature. “A Beautiful Poison” by Lydia Kang uses the Spanish Flu and World War I as the backdrop for a series of possible murders. “Moonstone: The Boy Who Never Was” by Sjón tells the story of a boy who lives in Reykjavik in 1918 at the edges of a society in flux. Just as Iceland is seeking its independence, the flu arrives on the island adding to the pandemonium. “This Mortal Coil” by Emily Suvada looks at what a modern day plague might be like. This science fiction thriller tells the story of a young gene hacker facing a gruesome pandemic after her geneticist father, who holds the key to the cure, is kidnapped.

The big question is will it happen again? Most experts consider another pandemic to be inevitable, the only questions being when, how big and what can we do to prepare? In “Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs,” Michael T. Osterholm paints a devastating picture and predicts that the next major pandemic “is most likely to come in the form of a deadly influenza strain.” “Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, From Cholera to Ebola and Beyond” by Sonia Shah and “The Next Pandemic: On the Front Lines Against Humankind’s Gravest Dangers” by Ali Khan both explore how a new pathogen could arise and develop into a pandemic. So, while scientists continue to work on a super shot for the flu, don’t forget to get your regular flu shot and stay healthy!

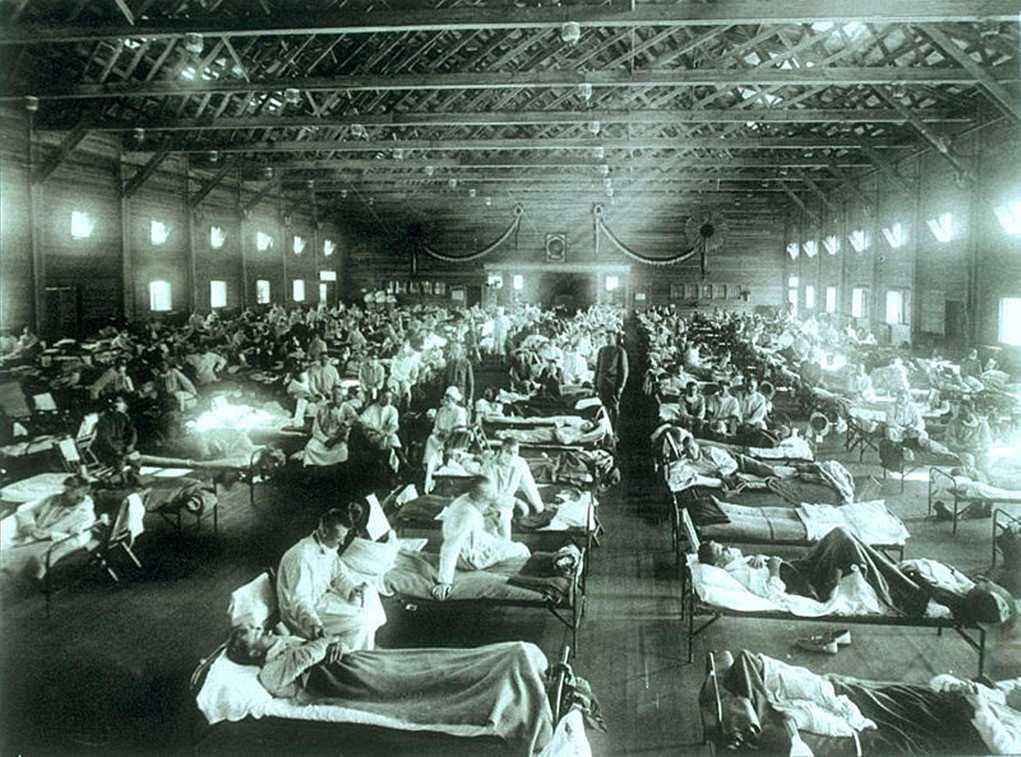

Image credit: National Museum of Health and Medicine, Emergency Hospital During Influenza via Wikimedia Commons (license)